2024 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the signing of the Venice Charter. The document, which was adopted by the International Congress of Architects and Conservationists in the Italian lagoon city in May 1964, also serves the Fortified Churches Foundation as a guideline for its conservation activities.

After the devastating catastrophe of the Second World War, monument preservation in the mid-twentieth century was faced with both difficult challenges and great opportunities. The idea of heritage conservation had only tentatively ventured from Great Britain onto the European continent when the war destroyed European cultural assets on a grand scale. Now, in the spirit of optimism of the 1960s, the Venice Charter was to set completely new standards in heritage conservation. The signatories used the Athens Charter from 1931, which had already dealt with similar issues in the interwar period, as a point of reference.

It is actually quite interesting that the Charter for the Preservation of Monuments, which sets out very strict standards, was signed in Venice of all places. Half a century earlier, the Campanile di San Marco was ceremoniously reopened in the harbour city: Reinforced concrete and the expertise of modern engineering, concealed in an enchanting shell that looks confusingly similar to the old Campanile that collapsed in 1902. In 1964, in the very city where this architectural misrepresentation of history was committed, it was stated on paper that “structural interventions must not alter the structural form. If reconstructions are necessary, architectural contributions from all relevant eras must be taken into account.” – Che peccato!

Conflicting interests

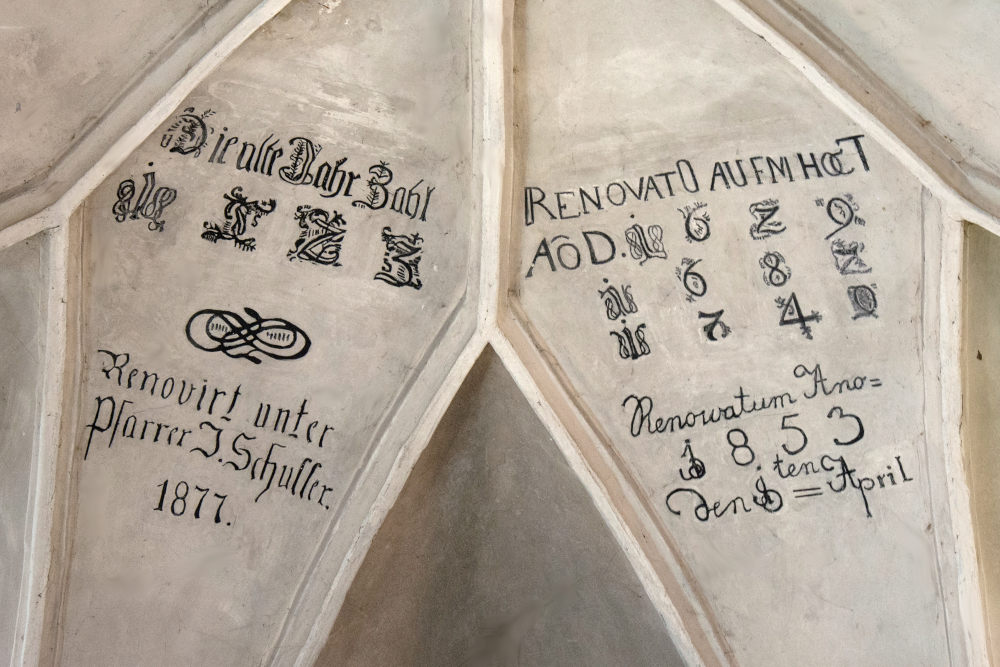

It would, of course, be disrespectful to denounce the Venetian councillors of the time alone in terms of cultural history. Historic preservation has always been caught up in a charged field of conflicting interests: User-friendliness, the available budget, bureaucracy, particular economic interests and, last but not least, unwritten laws (what would St Mark’s Square be without the Campanile?) are often in apparent or actual conflict with the noble aims of monument preservation. In the Transylvanian fortified church landscape, where churches, towers, gates and walls have not only been erected for centuries, but have also collapsed, we can regularly experience this tension.

One of the direct consequences of the signing of the Venice Charter was the founding of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in 1965. This non-governmental organisation advises UNESCO on world cultural heritage. The institution ICOMOS and, above all, the leading position held by the monument conservator and art historian Dr Dr h.c. from Sighișoara. Christoph Machat, the Transylvanian fortified churches of Biertan, Dârjiu (Székelyderzs), Viscri, Prejmer, Saschiz, Valea Viilor, Câlnic and the historic centre of Sighișoara were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List from 1993 onwards.

Venice could therefore be a lesson to us in many respects: The high standards of the Charter do not always lead to its uncompromising implementation. However, disputes over issues of heritage conservation can be conducted much more constructively thanks to the Venice Treaty than would be the case without this text. At the same time, we learn that mourning over the past is just as human as the desire to copy the old – even if this does not correspond to “pure doctrine”. The future will show what this means for Rodbav, Roadeș, Alțâna and other fortified churches in Transylvania affected by permanent damage.

Commentary und Photos: Stefan Bichler